(This is the second in a three-part series. Start at the beginning)

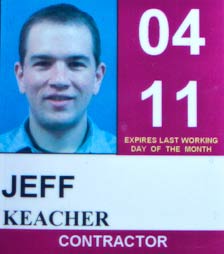

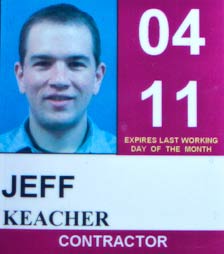

So there I was in the spring of 2010: a consultant. I was a hired gun, albeit one with substantial experience in The Company’s industry. It was bittersweet. (In keeping with tradition, I do not name employers or clients on this blog.)

All consultants are contractors, but not all contractors are consultants

By any objective measure, the gig was fantastic: good people, good project, and good money. I was useful and appreciated. However, I couldn’t shake the feeling that by failing to get Blurity to “ramen profitability,” I had embarrassed myself.

Time passed. Spring gave way to summer, and that in turn led to autumn.

I became increasingly comfortable with my role at The Company. There was a thrill from building something new. Likewise, there was camaraderie from working on a team with capable peers. It was –- dare I admit it — enjoyable.

The consulting gig made possible many good things: paying down student loans; replacing my old Subaru with a new Subaru; and visiting Canada, South Dakota, Baltimore, Boston, and New York City. Most importantly, the reliable income allowed me to rebuild my savings in preparation for another startup effort.

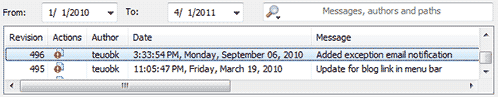

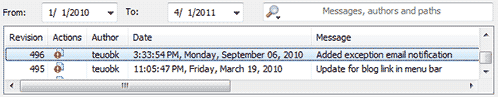

Unfortunately, saving for the future and doing work in the present were two different things. Blurity withered from neglect. I didn’t commit any code for it from March 19, 2010 to September 6, 2010. From about November 2010 to January 2011, the site’s payment pathway was totally broken; it’s rather telling that nobody noticed.

No commits on Blurity for six months

I was embarrassed by having to go back to Corporate America, but instead what I should have been embarrassed about was ignoring Blurity for six months. Sure, it was hard to go back to a computer in the evening having spent all day staring at one, but I should have been able to allocate at least a few hours a week to my startup. Had I invested just an hour a day between March 19 and September 6 in Blurity, that would have been the equivalent of working on it full time for a month. A lot can be accomplished in a full-time month. Maybe I wasn’t hungry enough.

Life was comfortable as a consultant. The hazard of becoming too comfortable loomed large. Fortunately, I took steps to ensure that the consulting engagement would not be extended indefinitely. The contract was specifically crafted so that I would be there for a short time, help my client, make some money, and then get out before I got hooked on the easy life. I wanted to make sure that I would go back to Blurity. Having certainty about the sunset was helpful for non-Blurity reasons, too.

I can’t understate how important it was to know that, no matter what happened, I would be gone in a year. Not because The Company was a bad place to be, but because it enabled me to approach nearly everything from an outsider’s perspective. I didn’t worry as much about office politics. I didn’t try to ensure my next project would be one of the “good” ones. I didn’t get too emotionally invested in product design decisions. It was fantastically liberating being a consultant instead of an employee, and moreover, being a consultant with an expiration date.

The end came on Friday — yesterday, as I write this. It’s hard to believe that 12 months went by so quickly. I’m technically on retainer through April, but I am no longer going in to the office on a set schedule.

I started the consulting gig reluctantly, came to terms with it, and grew to like it. Goodbyes are tough even when they are preordained.

As I walked out of the building on Friday, I couldn’t help but feel a bit sad. But then I reminded myself that the contract was always temporary; moving on was always part of the plan.

The sun peeked out from behind the clouds as I reached my car. I got in, opened the sunroof, and drove away.

I knew a new challenge was waiting for me on my home PC.

Update 8/22/2011: Almost five months have passed since I wrote this. I struggled with the third part, discarding several drafts, and in the end I decided that the setup I left at the end of this post won’t flow smoothly to the third part. Sorry about that.

(continue to part 3)

Recent Comments