Objective experience

A while back, there was a paper by Ericsson et al. that claimed that about 10 years of focused practice and experience were necessary to become an expert in something. Gladwell converted that figure to 10,000 hours, and some guy is trying out the theory investing that much time in learning golf. (Should be interesting to see if he gets more than fodder for a book out of the experience.) I’ve been thinking about how much time I’ve put into my own pursuits, and the numbers turned out to be surprisingly small.

Take hockey goaltending. I started playing goalie when I was 22 after graduating from Rose. I started from zero experience. I knew how to skate (though not well), and I had played some inline hockey, but I had never played organized ice hockey, and I certainly had never played goalie. That was seven years ago. I played for three seasons in Minnesota, didn’t play much for the two seasons I was in California, played off-and-on the first year I was back in Minnesota, and played a lot this past season.

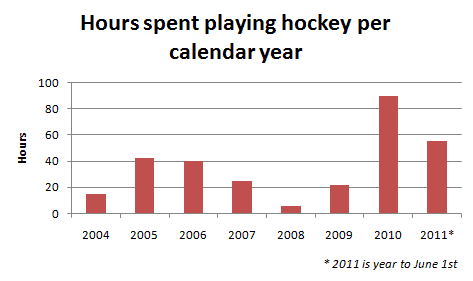

I tallied up the various organized games, pick-up games, practices, coaching sessions, and so on, and I figured out that I have spent just 295 hours playing goalie. In my entire life.

Hours spent playing ice hockey as a goalie by calendar year. The road trip will add about 90 hours to 2011's total.

That doesn’t seem like much. Consider that two months of full-time work at your office job will bring you to about 300 hours: would you consider yourself an expert in your profession after just two months? Or, looking at it a bit differently, what level of expertise does a summer intern have several weeks before the completion of his internship?

One might reasonably ask if that time, on rink or in office, was spent in an active, conscious attempt to improve. When I was an intern, I wasn’t even sure what I should be improving let alone actually improving it. With goaltending, I’ve been taking lessons over the past year, and I think that the deliberate practice and professional feedback has significantly improved my game. Unfortunately, that dedicated practice time has amounted to only a small fraction of my already limited experience on the ice.

Getting some pointers from my goalie coach this spring

Another example is backpacking. I think of myself as a capable backpacker. I’m comfortable in the woods, and I’ve spent lots of nights on solo trips in the wilderness. But am I an expert?

The numbers would suggest not. I’ve been doing regular backpacking trips only since 2007 (plus one trip to Philmont as a Scout in 1998). Excluding day-hiking, I figure I’ve covered about 280 miles while backpacking, over about 25 nights. Of those, about half were solo adventures, the most hazardous being my off-trail Badlands loop.

So, about a month, give or take, and well under 1000 miles. I feel more qualified than the numbers show, but I don’t think I’m anywhere near mastery. Maybe my confidence is due to the fact that I’m prepared when I go out; the 10 essentials have a permanent home in my pack. Perhaps it’s the amount of reading I’ve done on the subject, which has precipitated a significant evolution in my backpacking technique over the brief period I’ve been active. Still, an expert I am not.

Fortunately, I don’t rely on hockey or backpacking for my livelihood. My efforts to improve, particularly with hockey, are motivated simply by my desire to enjoy the activities more.

The thousands of hours spent studying, playing with, and working on computer technology, particularly software, are what have made me, if not a world-renowned expert, at least somebody competent in the field.

I wonder how the instant availability of so much information, tips, and tricks has affected the magic 10,000 hour mark. Decrease it due to expert advice, or increase it based on trial and error of bad advice? If so, by how much?

As far as becoming a master, I think it is important to realize that level of mastery over time is logarithmic. The more expert you become, the more difficult (more time) will be needed to increase your expertise by the same amount.