When robots flew

I was getting out of my car when a small plane buzzed over my head. Sam was parked in a grass field amongst many other Subarus and SUVs. The clouds above were breaking; it was going to be a hot day in Boulder.

I let my gaze follow the plane as it buzzed down the field. A wide gate was set in the air like a high-jumper’s bar, but instead of going over it, the plane went below it. In the distance, I could hear a roar of approval come up from the crowd of spectators. It would have been a trivial flight maneuver for a human, but no human was at the controls: the plane was flying autonomously.

When I think of robots, I think of autonomy. Sure, remote-controlled devices may technically qualify as robots, but that’s always seemed a bit like cheating to me. Imagine my thrill, then, when I found out that one of the largest competitions for amateur autonomous robot designers would be held an hour from my home in Denver.

The Autonomous Vehicle Competition draws participants from all over the country, and indeed, the world. It’s the effort of Sparkfun, a Boulder company that supplies electronic parts and kits to hobbyists of the robot kind. The competition is split into two different challenges: one requires navigating a ground course, roughly a square 100 ft on a side in a parking lot with obstacles; the other requires flying from a judging area over about 300 feet of water, crossing a peninsula, and returning to the origin. Each run is scored according to navigation time and extra challenges completed.

A ground-course vehicle leaps over the finish line

About a decade ago, my friend Joey and I made a GPS-guided self-driving Lego car for a class project. It was crude and didn’t work very well, but the thrill of having wrought into existence something that could actually drive itself around — well, I was all smiles even back then. The same enthusiasm was written on the faces of the hobbyists and engineers at the competition. I’m sure the same excitement is shared by those people working on the slightly bigger toys at Stanford and Google.

A large crowd of spectators packed the viewing stands and spilled out along the safety fences and grass. They were young and old, overwhelmingly male but not wholly without female representation. Some were entrants waiting for future heats; others were simply there for a passive thrill.

I spent some timing watching the aerial competition before moving to the ground track. Much to my surprise, the plane I had viewed upon my arrival was one of just a few fixed-wing entries. Though there was one true helicopter in the mix, the vast majority of aerial bots were quad- or octo-copters.

One of many quad-rotor entries; but unlike the others, a successful one

I’ll admit that a certain part of me wanted to see a big splash in the aerial competition, but that didn’t happen: the designs were surprisingly resilient, albeit not often successful. Also, the makers were generally standing by ready to cut over to manual control should everything go sideways.

Some entries ran the course and chalked up bonus points without breaking an electronic sweat; others failed to do much more than lift off the deck, hover for a few seconds, and set back down.

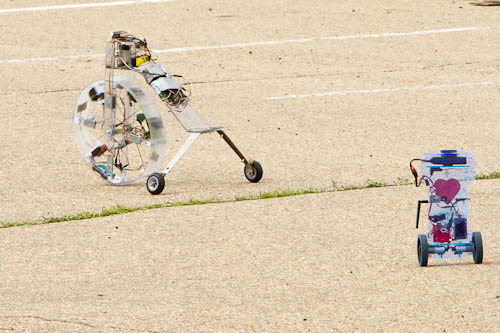

Over at the ground competition, the range of entries was a diverse affair. Everything from self-balancing two-wheeled contraptions the size of a coffee cup to a big-wheel tricycle made attempts on the course.

A “big wheel” is chased by a mini Segway

The course proved deceptively difficult. Very few of the ground vehicles successfully navigated the circuit. For at least half the entries, that meant failing to make the first of the four turns.

Some bots slammed into the far fence. Others turned too soon. A couple spun around at the starting line and zoomed off at high speed the wrong way around the course. The defending champion’s bot got loose in the infield, leading to a college-age nerdy guy running as fast as he could to chase it down, with the bot swerving to and fro as if it were trying desperately to escape some tyrannical master.

Spectators, spectators everywhere

Oh, and crashes! During the unlimited-class heat, I got to see the carnage I had paid (nothing) for: one smallish slammed itself into the far fence. Meanwhile, a large gas-powered go-kart bot gained speed off the starting line, started going for the first turn, and then apparently decided to give it a miss and accelerate into the fence — right where the small bot was hung up! The go-kart tried to get away and dragged the small bot a good 20 feet down the fence, leaving bent wire and miscellaneous bits of expensive plastic in its wake.

Crashes! A go-kart takes out a smaller bot, much to the amusement of the non-owners

During a lull in the competition, I took a walk through the team pit tent. At table after table, teams (and they were teams — I saw almost no solo entries) were hunched over laptops, sifting through telemetry, tweaking code, and mending broken bot bodies. The people were as dedicated as any I’ve seen in any other competition.

A college-age man works on his robot in the pit tent

And yet, the mood remained light. There was an overwhelming air of fun and excitement. Even the entrants whose bots had failed wore big smiles as they carried their creations off the course and developed stories of what went wrong and how the big victory got away. Fishing stories are not just for fishing.

Entries ranged from the simple (an 8-year-old boy made it half-way around the track with a Mindstorms-based four-wheeled bot) to the ultra-sophisticated (the university quad-copter teams running using GPS, computer vision, and other whiz-bang gadgetry). Complexity seemed to be poorly correlated to success, at least on the ground course: the slow and steady bots, apparently using dead-reckoning, generally performed more reliably than their fancier, faster, GPS-enabled, optical-sensor-encrusted cousins.

This young girl’s robot had no shortage of anthropomorphic flare

I felt more inspired than ever to make an entry for next year. How hard could it be?

Recent Comments